| Finding Flint Tools

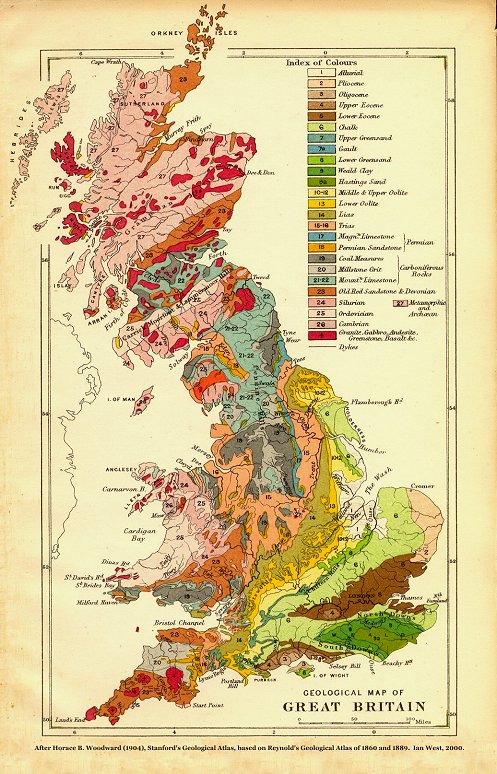

It’s important to understand the

geology of the area in which you are searching, so reading the

literature is an essential first step. Many prehistoric sites have been

documented and some of them remain accessible today, especially gravel

workings and ploughed fields.

Look in libraries and museums for local archaeological books,

papers and maps and descriptions of local discoveries in the past.

Even Victorian accounts can be a useful guide. Join your

local archaeological society.

Search the literature and the internet for references to previous

finds. If implements have been found before in a particular field

or quarry, that could indicate some kind of camp or settlement and

there may be other tools there.

Getting this information is often difficult and may well

take some persistence but it is the best indication you can get of

a fruitful place to search in your area. Some important

reference books are listed on the Books page.

There are also many valuable online resources. One such

website is ARCHI

which gives a county-by-county and town-by-town list of more than

100,000 archaeological sites in the UK.

Become a member of the Portable

Antiquities Scheme. The PAS site has a massive database with

photographs and details of thousands of find spots.

Where to look

Early humans often lived near rivers. As well as

providing drinking and cooking water, rivers also provided a

simple means of navigation and also opportunities to trap animals

who came to drink.

As a result, many artefacts ended up being swept into rivers,

rolled along, and deposited along with other, unworked, flints

into deposits known as river terrace gravels. Wherever such

terrace gravels are exposed in fields or extracted for building

use, there are often good places to search.

Most large rivers, such as the Thames, Medway and (ancient) Solent,

have left terrace gravels on the sides of the valleys that they

cut in historical times. Today those gravels are often dug for

building purposes or exposed in fields.

People in Mesolithic and Neolithic times often re-used flints that

they found lying on the surface, made flakes and left them behind

when they moved on. So you can find sites of habitation in

ploughed fields.

It is, of course, essential to get permission in advance from

the owners of the land or operators of the quarry.

Here's a tip that has worked for me many times. If you see

ploughed fields that look promising, study the Ordinance Survey

maps closely and keep your eyes open as you ride around the area (bicycle

is best). You will almost certainly find a footpath sooner

or later that crosses or runs close to your field. Walking the

footpath is a good way to do some reconaissance to see if you are

likely to find anything there and hence whether it is worth

approaching the landowner.

Design styles

It is important to familiarise yourself with the most common tool

designs of each period, so that you understand how the tools were manufactured.

For instance, in the early stone age, it is common to find hand

axes of so-called Acheulian design (name from St Acheul in France

where such implements were first discovered and described). These

are beautifully made and are artistic objects.

Paradoxically, in

Mesolithic times, hundreds of thousands of years later, the

commonest tools are flint flakes and scrapers.

These appear to be more crudely designed and made than the

elegant early implements. In fact they are a technological

advance, because by making flake tools instead of core tools,

humans made more efficient use of their flint - they got a

dozen tools where before the only got one. And small flakes could

be fitted into a wooden handle to make long knives, scythes and

even saws for felling trees.

Be persistent

As with finding fossils of all kinds, it’s a question of

“getting you eye in” so don’t give up too easily at the

beginning. At first you may look despairingly around a field and

see only ordinary flints. With practice, you may come to realise

that the ordinary looking field is actually littered with

implements, once you know what you’re looking for and how they

appear in situ, and you will wonder why you couldn’t “see”

them before.

Logging finds

If you wish your finds to be of scientific value now or in the

future, you may wish to buy a handheld GPS positioning device.

This can help you locate places on an Ordinance Survey map very

accurately, and also to log your finds exactly. Some

devices can be pricy, but there are some lower cost devices such

as the Garmin eTrex H Handheld GPS. You can also look on

eBay for second hand devices.

How to plot a findspot using the Garmin Etrex

Switch on (power button) and you'll see the ‘satellite page’.

When the receiver is ready to use (once it has tracked satellites)

it will display the message ‘ready to navigate’. Use the

‘page’ button to get to the ‘menu’ (4 clicks of the

button). Then select ‘mark’ using the ‘enter’ button. The

National Grid Refrenece (NGR)

of the findspot (e.g. TQ 12345 67890) will be shown below a man

holding a flag. Press the ‘enter’ button when ‘ok’ is

highlighted if you want to save this ‘waypoint’.

To use a GPS device when you find a flint do the following:

Take a reading from your GPS device. Write the reading on the tag

of a collecting bag. Place the find in the bag and seal it.

The latest generation of digital cameras (such as Panasonic)

can register the GPS position at which a photo was taken. If

you can afford it, this simplifies recording find positions

considerably as all you have to do is photograph each find in

situ, making sure it is clearly identifiable.

|

Gravel workings (above) and ploughed fields (below) are often

fruitful places to search - as long as you get permission first!

Understanding the geology of the area in which you are

searching is essential. Old maps, papers and books are

invaluable sources of reference.

|